ReactiveX | Part I: The Iterator & Observer Pattern

11 Sep 2020Reactive programming is a programming paradigm that deals with data flows and the propagation of change. It helps you build a message-driven application that scalable and extensible. A lot of frameworks/ libraries turn out to become magically Reactive these days.

In this series, I will try to explain what is Reactive Programming, it’s application and implementation. The first post would be about the things behind the scene: Iterator & Observer Pattern.

For ease to follow, I will use Java to demonstrate. So you should have some knowledge about it.

Iterator Pattern

Basically, the Iterator pattern is used for traversing elements of a collection, without exposing it’s underlying representation.

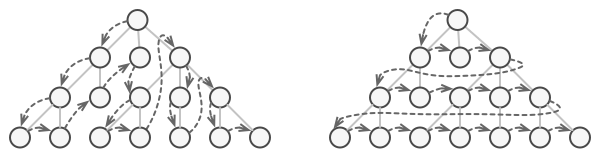

In real world application, we usually use various type of data structures: Array, List, Stack, Queue, Tree, HashMap, … and even your own data structure. The way to traverse between them is different.

Assume that we have a Book class

class Book {

String title;

String author;

public Book(String title, String author) {

this.title = title;

this.author = author;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return "Book{" +

"title='" + title + '\'' +

", author='" + author + '\'' +

'}';

}

}

Here is how we iterate over an array of book in Java:

for (int i = 0; i < bookArr.length; i++) {

Book book = bookArr[i];

System.out.println(book.toString());

}

And here is how we do the same thing with a list of book:

for (int i = 0; i < bookList.size(); i++) {

Book book = bookList.get(i);

System.out.println(book.toString());

}

As you can see, with different types of collection, the way we traversing must be slightly modified. Let’s create a new data structure called BookSinglyLinkedList and create a method add inside.

class BookSinglyLinkedList {

BookNode head;

void add(BookNode newNode) {

if (head == null) {

head = newNode;

} else {

BookNode current = head;

while (current.next != null) {

current = current.next;

}

current.next = newNode;

}

}

}

You need some understanding about singly linked list. To find out more about it, please check it here

And our BookNode class:

class BookNode {

Book book;

BookNode next;

BookNode(Book book) {

this.book = book;

}

}

So how can we iterate over our new BookSinglyLinkedList, or further, how can we iterate over any kinds of book collection?

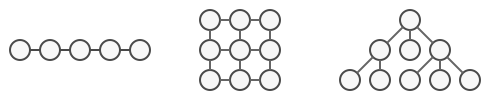

This is where the Iterator pattern involves in. Class diagram:

Usually, an iterator will have 2 methods: hasNext and next. This is our BookIterator

interface BookIterator {

// indicating if there are more elements to iterate over

boolean hasNext();

// return the next object

BookNode next();

}

We also want to make sure that any types of book collection is iterable, which means that they should have an iterator inside. Let’s create another interface named BookIterable, then our BookSinglyLinkedList will implement it. We’ll also create an inner class named BookSinglyLinkedListIterator. The iterator class should implement our BookIterator interface.

interface BookIterable {

BookIterator getBookIterator();

}

class BookSinglyLinkedList implements BookIterable {

BookNode head;

@Override

public BookIterator getIterator() {

return new BookSinglyLinkedListIterator(this.head);

}

void add(BookNode newNode) {

if (head == null) {

head = newNode;

} else {

BookNode current = head;

while (current.next != null) {

current = current.next;

}

current.next = newNode;

}

}

static class BookSinglyLinkedListIterator implements BookIterator {

BookNode runningNode;

BookSinglyLinkedListIterator(BookNode node) {

runningNode = node;

}

@Override

boolean hasNext() {

return runningNode != null;

}

@Override

BookNode next() {

BookNode currentNode = runningNode;

runningNode = runningNode.next;

return currentNode;

}

}

}

So what happened here? We hid the traversing logic inside our iterator class, and exposed the hasNext and next methods. With this approach, any “iterable” collections can be iterated over using the iterator object without knowing their implementation.

Let’s create another collection named BookStack and do the same thing as the singly linked list.

class BookStack implements BookIterable {

BookNode top;

@Override

public BookIterator getIterator() {

return new BookStackIterator(this.top);

}

void push(BookNode newNode) {

if (top != null) {

newNode.next = top;

}

top = newNode;

}

static class BookStackIterator implements BookIterator {

BookNode runningNode;

BookStackIterator(BookNode node) {

this.runningNode = node;

}

@Override

boolean hasNext() {

return runningNode != null;

}

@Override

BookNode next() {

BookNode currentNode = runningNode;

runningNode = runningNode.next;

return currentNode;

}

}

}

And the our demo main method:

public static void main(String[] args) {

Book donQuixote = new Book("Don Quixote", "Miguel de Cervantes");

BookNode donQuixoteNode = new BookNode(donQuixote);

Book harryPotter = new Book("Harry Potter", "J.K.Rowling");

BookNode harryPotterNode = new BookNode(harryPotter);

BookSinglyLinkedList bookList = new BookSinglyLinkedList();

bookList.add(donQuixoteNode);

bookList.add(harryPotterNode);

Book theLittlePrince = new Book("The Little Price", "Antoine de Saint-Exupéry");

BookNode theLittlePrinceNode = new BookNode(theLittlePrince);

Book theHobbit = new Book("The Hobbit", "J. R. R. Tolkien");

BookNode theHobbitNode = new BookNode(theHobbit);

BookStack bookStack = new BookStack();

bookStack.push(theLittlePrinceNode);

bookStack.push(theHobbitNode);

// Starting to iterate over the list and the stack

BookIterator listIterator = bookList.getIterator();

System.out.println("Iterating over the list");

while (listIterator.hasNext()) {

System.out.println(listIterator.next().book.toString());

}

System.out.println("Iterating over the stack");

BookIterator stackIterator = bookStack.getIterator();

while (stackIterator.hasNext()) {

System.out.println(stackIterator.next().book.toString());

}

}

As you see, the way we iterating over the list and the stack is the same. The output of our program:

Iterating over the list

Book{title='Don Quixote', author='Miguel de Cervantes'}

Book{title='Harry Potter', author='J.K.Rowling'}

Iterating over the stack

Book{title='The Hobbit', author='J. R. R. Tolkien'}

Book{title='The Little Price', author='Antoine de Saint-Exupéry'}

In Java, we’ve already have java.lang.Iterable and java.util.Iterator class, you can check it out yourself.

The applications of Iterator pattern:

- Use the Iterator pattern when your collection has a complex data structure under the hood, but you want to hide its complexity from clients.

- Use the pattern to reduce duplication of the traversal code across your app.

- Use the Iterator when you want your code to be able to traverse different data structures or when types of these structures are unknown beforehand.

Observer pattern

Observer pattern is used when there is one-to-many relationship between objects such as if one object is modified, its dependent objects are to be notified automatically.

Imagine that we’re having a weather station for gathering the weather data every hour. And we’re also having multiple device that consuming the data from the station, and display it in different way. They are TV, PC and Smartphone.

Let’s create 3 classes for these devices and 1 class for carrying the weather data

Weather.java

public class WeatherData {

double humidity;

double temperature;

double pressure;

public WeatherData(double humidity, double temperature, double pressure) {

this.humidity = humidity;

this.temperature = temperature;

this.pressure = pressure;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return "WeatherData{" +

"humidity=" + humidity +

", temperature=" + temperature +

", pressure=" + pressure +

'}';

}

}

PC.java

public class PC {

void display(WeatherData weatherData) {

System.out.println("Weather data from PC is: " + weatherData.toString());

}

}

TV.java

public class TV {

void display(WeatherData weatherData) {

System.out.println("Weather data from TV is: " + weatherData.toString());

}

}

SmartPhone.java

public class TV {

void display(WeatherData weatherData) {

System.out.println("Weather data from SmartPhone is: " + weatherData.toString());

}

}

Inside our WeatherStation class, we create a method to update the weather data and send it to our display devices

public class WeatherStation {

PC pc;

TV tv;

SmartPhone smartPhone;

void measureChanged(WeatherData data) {

pc.display(data);

tv.display(data);

smartPhone.display(data);

}

}

The problem now is that what if we got more & more kinds of device, and what if some devices don’t want to get the data anymore?

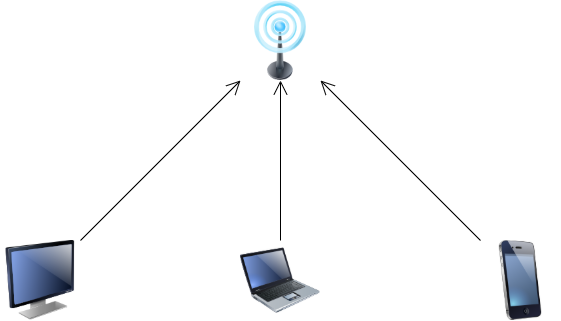

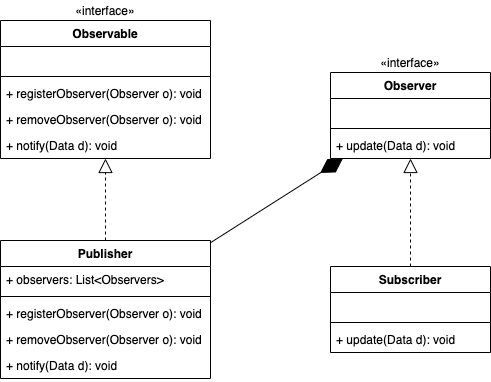

The Observer pattern will help you to manage them. The diagram:

The steps are:

- All devices will “subscribe” to our

WeatherStation. So they become “subscriber” now. - Whenever our

WeatherStationreceive new data, it will “publish” it to it’s subscribers. Generally, theWeatherStationplays as a “Publisher” here. - If one of our device don’t want to receive data anymore, then can just simply unsubscribe the

WeatherStation.

Thinking about how you use YouTube daily. If you want to get notify when some YouTubers upload videos, you can just subscribe them. Then if you’re not interested anymore, you can just unsubscribe them.

Let’s create a WeatherObserver interface:

interface WeatherObserver {

void update(WeatherData data);

}

WeatherObserver here is our consuming data device. Another name can be WeatherSubscriber. All of our devices will need to implement this interface.

For simplicity, we now only update the PC class, cause everything is the same for others.

public class PC implements WeatherObserver {

void display(WeatherData weatherData) {

System.out.println("Weather data from PC is: " + weatherData.toString());

}

@Override

public void update(WeatherData data) {

this.display(data);

}

}

Now we’ll create an interface named WeatherObservable interface, and make our WeatherStation implement it. You can think an observable object is an object that can be watched by it’s clients/subscribers.

interface WeatherObservable {

void registerObserver(WeatherObserver observer);

void removeObserver(WeatherObserver observer);

void notify(WeatherData data);

}

public class WeatherStation implements WeatherObservable {

List<WeatherObserver> observers;

public WeatherStation() {

this.observers = new ArrayList<>();

}

@Override

public void registerObserver(WeatherObserver observer) {

observers.add(observer);

}

@Override

public void removeObserver(WeatherObserver observer) {

observers.remove(observer);

}

@Override

public void notify(WeatherData data) {

for (WeatherObserver observer : observers) {

observer.update(data);

}

}

void measureChanged(WeatherData data) {

this.notify(data);

}

}

Inside the WeatherStation, we’re maintaining a list of our observers. Notice that we’ve updated the measureChanged method: when it’s called, all our observers will get updated with the data. The registerObserver & removeObserver methods is used for adding/removing subscriber from the list.

Our demo main method:

public static void main(String[] args) {

WeatherStation station = new WeatherStation();

PC pc = new PC();

TV tv = new TV();

SmartPhone smartPhone = new SmartPhone();

// Register observers

System.out.println("Register observers");

station.registerObserver(pc);

station.registerObserver(tv);

station.registerObserver(smartPhone);

// Update data

System.out.println("Notify data");

station.measureChanged(new WeatherData(70, 30, 1000));

// Remove observe

station.removeObserver(tv);

System.out.println("Notify data after removing the tv");

station.measureChanged(new WeatherData(75, 32, 1000));

}

And the output:

Register observers

Notify data

Weather data from PC is: WeatherData{humidity=70.0, temperature=30.0, pressure=1000.0}

Weather data from TV is: WeatherData{humidity=70.0, temperature=30.0, pressure=1000.0}

Weather data from SmartPhone is: WeatherData{humidity=70.0, temperature=30.0, pressure=1000.0}

Notify data after removing the tv

Weather data from PC is: WeatherData{humidity=75.0, temperature=32.0, pressure=1000.0}

Weather data from SmartPhone is: WeatherData{humidity=75.0, temperature=32.0, pressure=1000.0}

When to use Observer pattern:

- Use the Observer pattern when changes to the state of one object may lead to changing in other objects.

- List subscribers is unknown beforehand.

- Observer only need to watch the data for a specific time.